(What to do when you are suddenly responsible for years of Process Safety neglect.)

It’s a scene I come across time and time again: a newly assigned PSM/RMP coordinator staring at me with shock as we progress through their Compliance Audit, Process Hazard Analysis, or 5yr Independent Mechanical Integrity Inspection.

“I didn’t know things were this bad!” they’ll say under their breath, once the situation starts to become a little clearer to them. You can imagine them standing at the bottom of a deep, dark hole wondering how they’ll ever make it back to fresh air and bright sunshine they thought was all around them just a few hours ago. For those of you that have read my previous post on the “Stages of PSM Grief,” this is the moment they are breaking past the Denial stage.

It can be heartbreaking to watch the mixture of Anger, Bargaining and Depression, especially if you remember what it felt like to be there yourself.

Often, I will have to re-assure them that this is just the start of the process and the beginning isn’t going to be fun. Sometimes I’ll quote Winston Churchill.

What’s really important is that we understand there will be a way out if we remain calm and plan intelligently. Unsurprisingly, you need a process to address Process Safety issues.

So, let’s start planning our escape! We’re going to move slowly at first, with ever-increasing confidence, and once we get rolling we’re going to start seeing daylight.

Here’s how our progression will look:

- Assess the situation

- Prioritize the issues

- Formulate the plans & assign responsibility

- Implement, Implement, Implement!

Part 1: Assess the situation

Obviously, if you are in the middle of (or have just gone though) an audit or inspection, you’re well on the way! If you are recently assigned to this coordinator role and you don’t have a recent compliance audit, PHA, and MI report, then these are good places to start.

Assessment is really two parts which can share the same ground.

- Compliance: Where you are in relation to where you need to be.

- Culture: Where you are in relation to where you want to be.

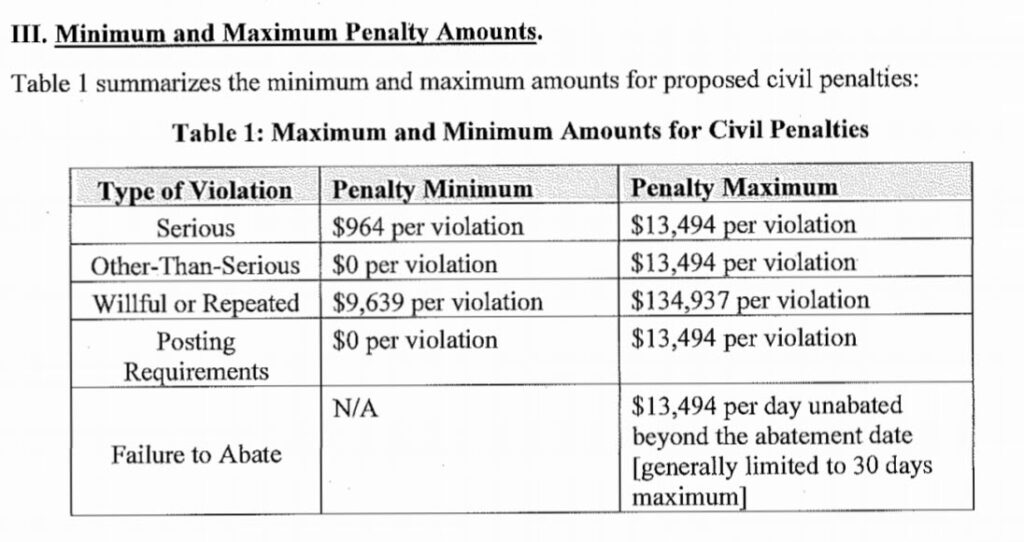

I can’t stress this enough – being compliant is not some lofty place. It is the bare minimum of safety allowed under the law. How far past “my company isn’t violating federal and state law” you want to go depends a lot on the culture of your organization. For example, companies with a brand to protect tend to aim a lot higher than those that don’t. Companies that are barely making ends meet tend not to have a lot of resources to bring to bear on things that aren’t strictly required.

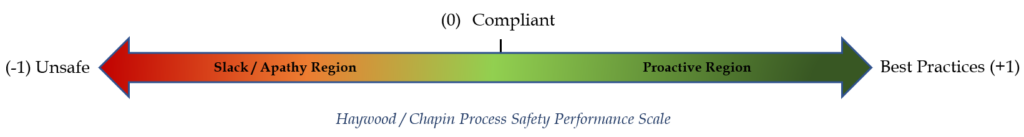

Recently, based on a conversation with colleagues, I half-jokingly formulated what I called the Haywood / Chapin Process Safety performance scale as a visual tool. Note that you get a score of zero for being compliant because that’s the baseline. We’re not going to go around congratulating each other for not violating Federal and State laws. Additionally, we aren’t going to give ourselves any credit for trying – only for results: Safety & compliance aren’t kindergarten so we aren’t giving out participation trophies.

Note: It’s common at this point to try and figure out how the company got themselves in this hole, but there is usually very little of value that comes out of this conversation. If the same people, and the same processes are in place, don’t expect different results unless they are willing to change. Don’t get your hopes up just because people want to change. What matters is if they are willing to put in the work to change. If only wanting to change was enough to effect change, nobody (including me) would be carrying around a few extra pounds.

Part 2: Prioritize the issues

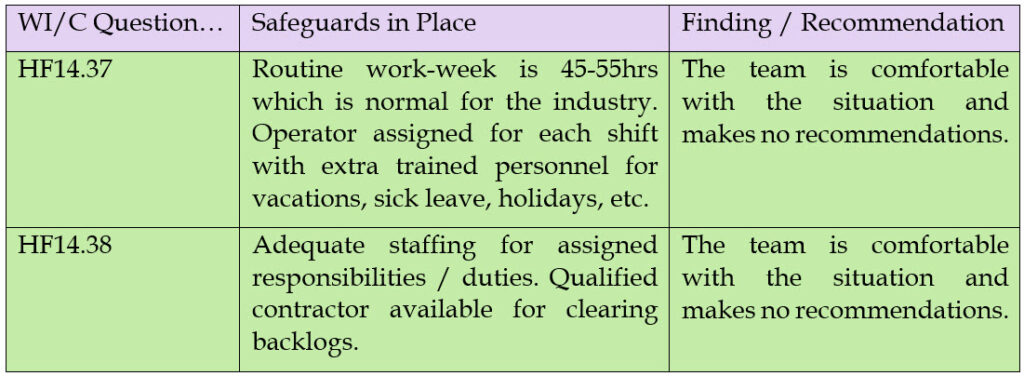

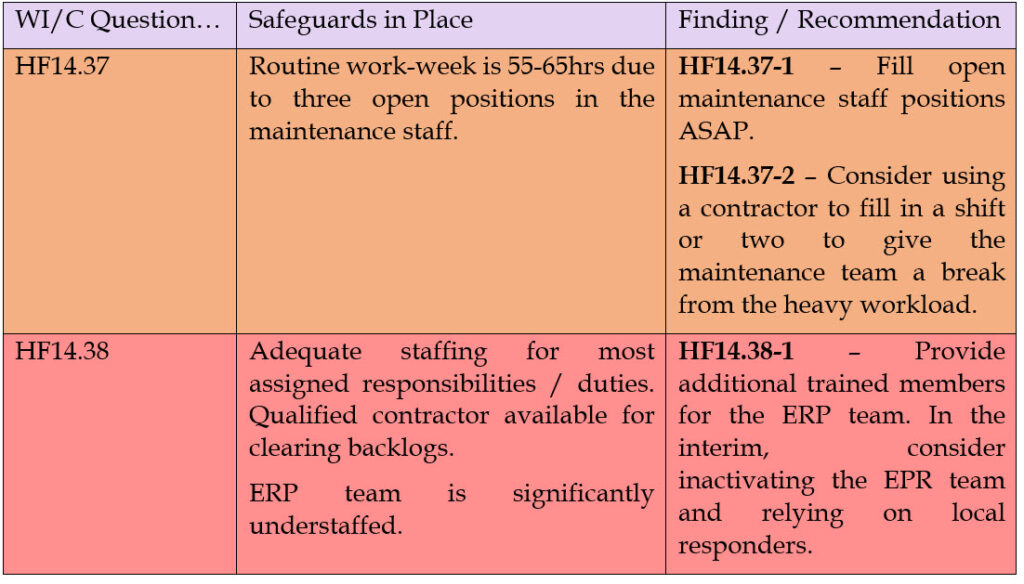

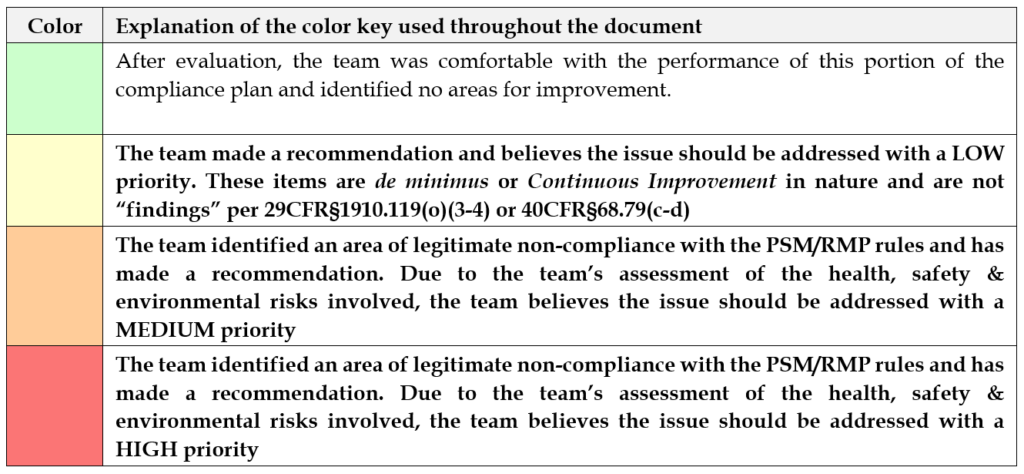

All right. Now you have collected all the deficiencies so you know the ground you need to cover to get where you want to be – or, in our analogy, how far it is to get out of the hole you are in. Now we need to figure out in what order we need address these issues. Hopefully, your audits have given you some guidance here. For example, this is the color code I use for my compliance audits:

Obviously in this scheme, we’d focus our efforts on the red items, then the orange, etc. You will want to prioritize the actions you take based on the risk to your employees, your community and your business. I strive to get the “buy-in” from the audit team during the audit itself so this step is pretty much done for you. However, you may have a lot of findings & recommendations to deal with so further prioritization can be useful.

Part 3: Formulate the plans & assign responsibility

Formulating the plan(s) is one of the most difficult parts of the whole endeavor: How do we address all the issues we’ve found? We’re going to use a few strategies to help us formulate our plan:

- Group where appropriate

- Don’t reinvent the wheel

- Don’t make Perfect the enemy of the Good

- Leverage strengths & Avoid weaknesses

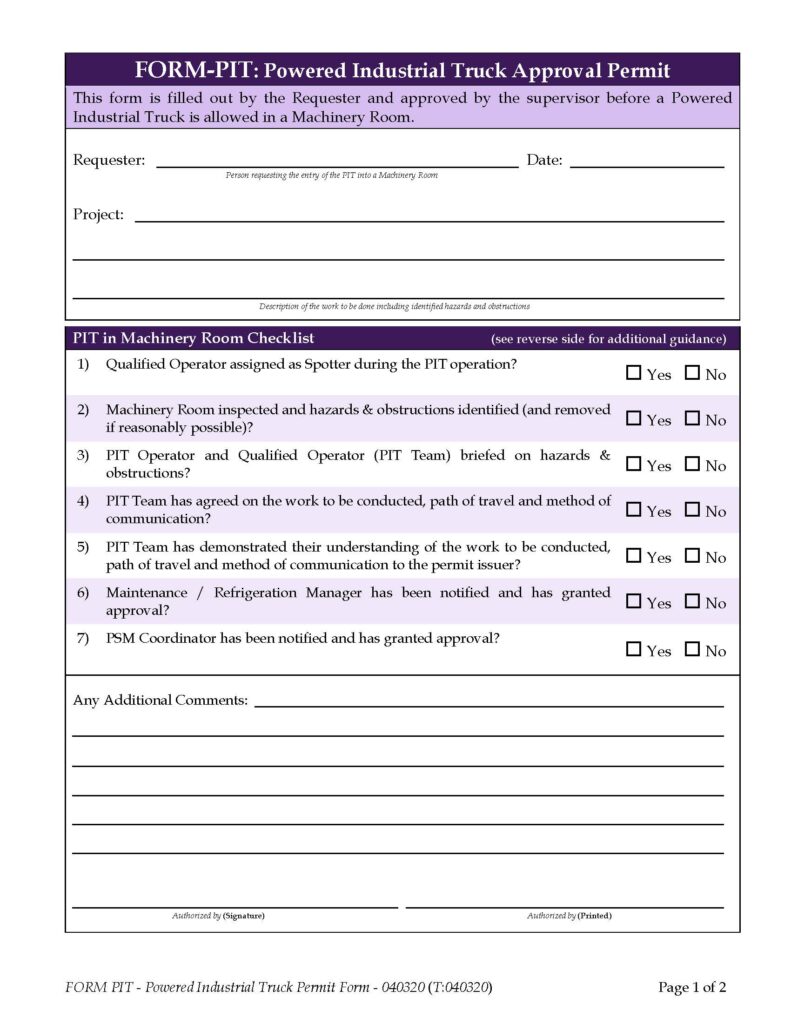

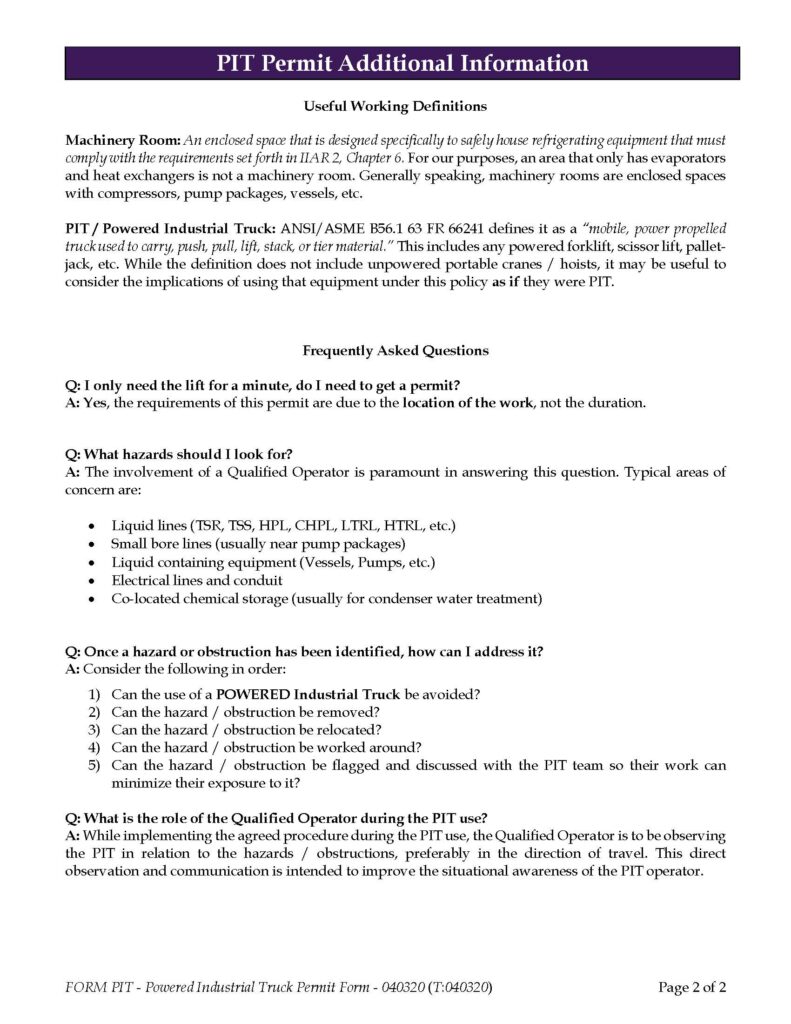

Grouping: One thing you may find is that a common root cause means you can group items. For example, if I have a poorly constructed MI inspection with 600 pipe label recommendations I can view each of those as individual recommendations or I can decide that the root cause is that we don’t have a system to ensure adequate pipe labeling. For me, I’d rather put a system in place to address that widespread deficiency than rely on just fixing the issues someone else found thus ensuring I’ll need them to find them next time too! For the example of pipe labeling, I would train my operating staff on the requirements of IIAR B114 and place a label check in the annual unit inspection work order. Properly implemented that system ensures that the issue will be addressed in the next year and will continue to be addressed regularly thereafter.

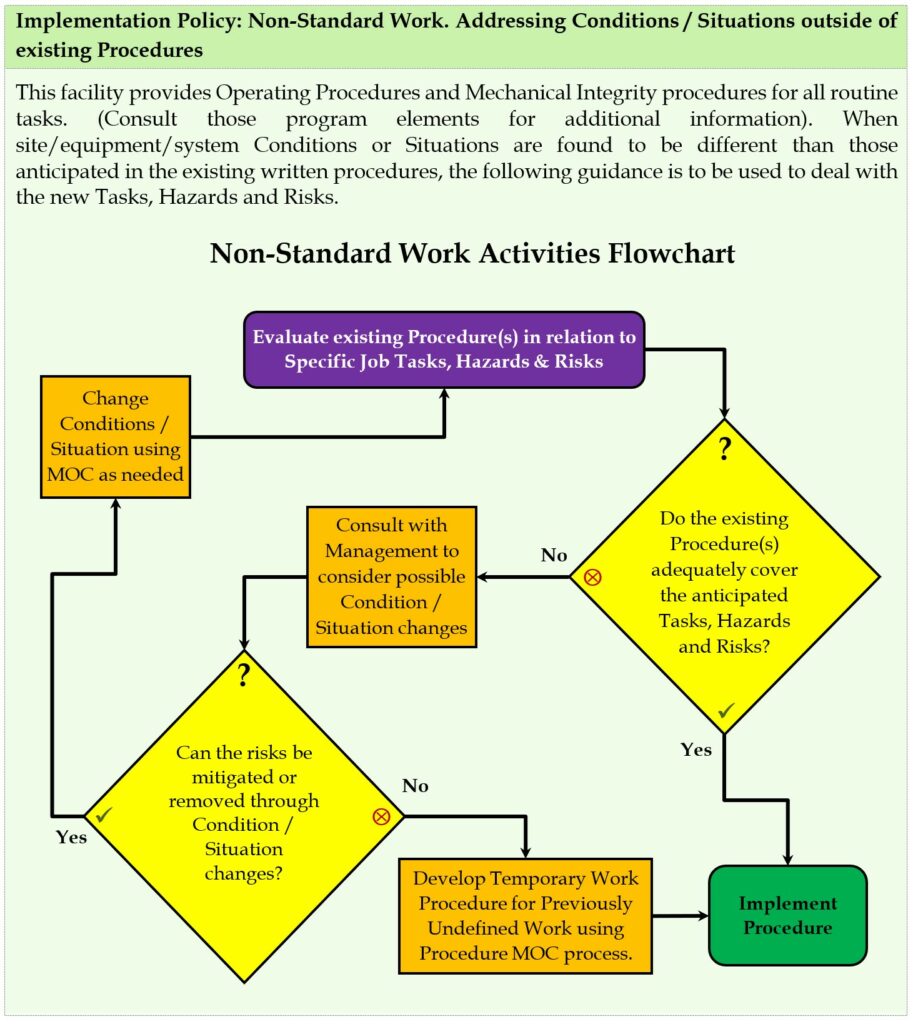

Don’t reinvent: There’s plenty of freely available templates for nearly all programs, procedures, work orders, etc. you may need. Don’t waste your time creating a policy or procedure from scratch when you can often use a pre-made one to address the issue with little or no change.

Don’t make Perfect the enemy of the Good: Sometimes altering a simple policy that solves the problem 99% of the time to one that solves it 100% of the time turns it into a lengthy and confusing mess. Policies and procedures aren’t meant to completely replace independent thought – they should be designed to guide it. We should bias our efforts towards “good enough” at first and strive towards perfection over time with continuous improvement.

Leverage Strengths & Avoid Weaknesses: Tasks should be assigned to people based on their competencies. For example, if you have a good core competency in your staff for writing SOPs, then by all means go ahead and write them. But if you don’t have anyone with that experience, maybe outsource that issue so their time is spent on the things they are already good at. Using a stock template and the needed PSI, my personal average for SOPs is about 1.5 hours. I’ve seen relatively competent people take 10 hours or more on the same SOP. The difference is that I wrote the template and have used it thousands of times. On the other hand, I’ve been known to take 3x as long as a skilled operator to change oil filters on a compressor because I’ve only done it a handful of times.

Assigning Responsibility is crucial. What we want is to have someone own the solution. Even if you assign a task to an outside consultant or contractor, make sure someone in-house is assigned the responsibility for the task to ensure they keep that 3rd party in-line and on-schedule.

Also keep in mind that this is a great place in this process to manage expectations. Often a facility has been neglecting their PSM duties for decades but seems shocked that the newly assigned PSM coordinator can’t solve the problem in a few weeks. Let’s just say that if it took 10 years to dig the hole, it’s not realistic to expect anyone to dig you out of it quickly.

Part 4: Implement, Implement, Implement!

Prussian military commander Helmuth van Moltke is famous for saying that “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.” You are never going to get anywhere until you go out there and start implementing your plans. You can’t build a reputation on what you plan to do.

Don’t be hesitant to reassess and change the plan if things aren’t going well.

One of the most important things you can do during this part of the process is having regular PSM meetings. Make sure everyone assigned a task is asked about their progress. It may seem like a waste of time, but it’s also a good practice to go over the things you have already accomplished. I recommend this for two reasons:

- It gives everyone a chance to confirm that the implemented solution to the issue worked

- It reminds you that progress is being made and you will eventually get out of the hole if you keep on!

As always, if there is anything we can do to help, please contact us!